Varicella (chickenpox) Vaccine

I don’t know about you, but I REMEMBER getting the chickenpox as a young child. It was itchy and awful. And oatmeal baths! Oh, the oatmeal baths!!

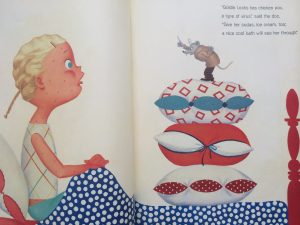

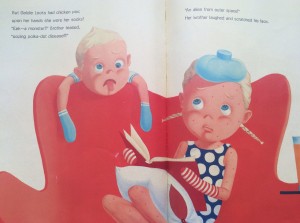

Because this is most often a children’s disease, I thought it would be appropriate to litter this post with the some of the cute photos from one of my daughter’s favorite children’s books: Goldie Locks has Chicken Pox by Erin Dealey, illustrated by Hanako Wakiyama.

Although the illustrator makes chicken pox look cute, it’s anything but. Thankfully, due to the vaccine our kids don’t ever need to experience the chickenpox…

Chickenpox is caused by a virus called the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), which is part of the herpesvirus family. The same virus that causes chickenpox can cause shingles later in life. The virus is called varicella when it causes chickenpox, then the virus hides in your body and it gets called zoster when it flares back up and causes shingles. There is also a vaccine for shingles called the zoster vaccine, which you may get should you choose to at around the age of 65 (but, that’s for another post).

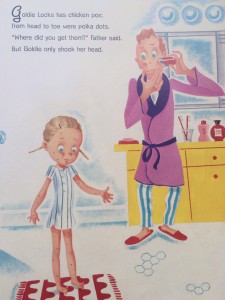

‘Where did you get them?’ Father said.

But Goldie only shook her head.”

The chickenpox is spread very easily from person to person. Your child can contract chickenpox by getting the fluid from someone’s chickenpox blister into their body or by inhaling droplets with viral particles spread by a cough or sneeze.

Before the notorious chickenpox rash appears, your child would come down with a fever, headache, and stomach ache–symptoms that are common to many other diseases. However, about 10-21 days after you child has had contact with someone with chickenpox and has become infected, he would develop between 250 to 500 red spots with small, itchy, fluid-filled blisters. These blisters normally start on the face, middle of the body, or the scalp, then after a day or so become cloudy and scab. Following that, new blisters form in groups, often appearing around the mouth, in the vagina, and on the eyelids. If your child had prior skin problems, such as eczema, he may get thousands of blisters with the chickenpox.

If your child should get the chickenpox, there’s not much you can do but keep him comfortable. Try to keep him from scratching the blisters and keep clothing and bedding loose and light. Give him lukewarm baths with oatmeal or cornstarch and apply soothing moisturizer. Avoid exposure to heat and humidity, if possible. And if needed, over-the-counter oral antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can be given, as well as hydrocortisone cream applied on itchy areas. Do NOT give aspirin or ibuprofen to someone who may have chickenpox!!

You should not give your child aspirin up to six weeks after getting the chickenpox. The use of aspirin has been associated with Reyes syndrome–a potentially fatal complication that effects that brain. Ibuprofen, also, can lead to more severe secondary infections. If anything, acetaminophen (Tylenol) can be given for pain relief.

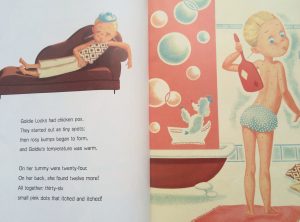

On her tummy were twenty-four. On her back, she found twelve more! All together: thirty-six small pink dots that itched and itched.”

Keep your sick child home from school and/or daycare until the blisters have dried out and crusted over.

The crusted sores will not leave scars unless they have become infected with bacteria due to excessive scratching. And most children recover fully without complications. Once the child has fully recovered, the virus does not leave the body. It remains hidden–dormant–for many years. It can remain dormant for the person’s entire lifetime, or come back again, in times of extreme bodily stress. If it should come back again, the virus causes an extremely painful disease called shingles. This occurs in about 1 out of every ten adults.2 You need not worry about shingles in your child right now, as this disease usually shows up late in life. (More on shingles and the shingles vaccine at a later date.)

Most cases of chickenpox are seen in children under ten.4 If you were to get chickenpox as a teen or adult, you would often be much, much more sick that if you were to get it as a child. Most children who get chickenpox young, have mild cases and recover within a few weeks. Severe cases are more common in children whose immune systems are challenged due to other illnesses, medications, chemotherapy, and steroids.

Complications that can occur from the chickenpox:

- Hospitalization (2-3 people out of 1,000 cases)1

- Serious bacterial infections of skin lesions are the most common cause of hospitalizations.

- Encephalitis (1.8 people out of 10,000 cases)1 and may lead to seizures and coma

- Reye’s Syndrome

- Myocarditis–inflammation of the heart muscle

- Pneumonia–usually viral, but can be bacterial. Bacterial more common in children under one.1

- Transient arthritis

- Central nervous system (CNS) manifestations–range from aseptic meningitis to encephalitis.1 The most common CNS complication is cerebellar ataxia, which involves a very unsteady walk and generally has a good outcome.

- Death in 1 out of 60,000 cases1

- Rare complications of varicella: aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, thrombocytopenia, hemorrhagic varicella, purpura fulminans, glomerulonephritis, myocarditis, arthritis, orchitis, uveitis, iritis, and hepatitis.1

Women who get the chickenpox during pregnancy can pass the infection to the unborn baby. Mothers who have not been vaccinated or have not had chickenpox themselves, and who contract chickenpox during pregnancy may have babies born with congenital varicella syndrome (CVS). These babies may have low birth weight, skin scaring, and/or eye and neurologic abnormalities. Babies born with extreme CVS have a 30% mortality rate.1 If the mother is infected in the first 20 weeks of the pregnancy, the risk of having a child born with CVS is higher.

However, babies born to mothers who have had the varicella vaccine are not very likely to catch the chickenpox before they are one year old and are likely to have milder cases if exposed to the chickenpox.4 This is due to memory antibodies passed from the mother to the unborn child. Children who do not receive the vaccine and get chickenpox under the age of one are also susceptible to severe infection.

The varicella vaccine usually prevents the chickenpox disease entirely or makes the disease VERY mild if your child should catch it. No vaccine is 100% effective, however the varicella vaccine keeps 80-90% of people who are vaccinated completely protected.1

Some children who get the vaccine will still get the chickenpox if exposed to it, however because of the vaccine they will recover much more quickly and have only a few pox (fewer than 30).4 The vaccine, however, always prevents severe infection!

Getting your child vaccinated is the best way to prevent him from getting the chickenpox, as well as keep the chickenpox virus out of the community. Two doses of the varicella vaccine are recommended for anyone who has not had the vaccine. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that children be given the first does at 12-15 months of age and the second dose at 4-6 years of age (may be given earlier, if at least 3 months after the 1st dose). Children and adults that are 13 years old and older who have not had chickenpox or the vaccine should get two doses at least 28 days apart. All adults who have not had the chickenpox or the vaccine should get vaccinated! Contracting the chickenpox is much worse as an adult. Contact your doctor to make sure you have been vaccinated properly.

If you are in need of the vaccine as an adult and you are pregnant, you must wait until after the baby is born to get the vaccine. Also, you should wait until a month after you have been vaccinated to get pregnant. As stated above, the varicella virus is potentially harmful to the unborn child.

There is also a combination vaccine called the MMRV vaccine. This combines the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine with the varicella vaccine. For more information on this vaccine, check out the MMR post, here.

As with all vaccines, getting the varicella vaccine is much safer than getting the actual disease. Most people who get vaccinated do not have complications from the vaccine, however some side effects have been reported:

- Soreness, redness, or swelling where the shot was given

- Fever

- Mild rash or several small bumps after vaccination (4-6% get about 5 lesions.)1

- Seizure (jerking and staring spell) that may be caused by fever. However, this may not be related to the vaccine, but a fever induced by the body making a memory response to the weakened virus in the vaccine.

- Serious side effects from chickenpox vaccine are extremely rare. They may include severe brain reactions and low blood count. These side effects happen so rarely that experts cannot tell whether they are caused by chickenpox vaccine or not.1

Should you our your child develop serious side effects to this or any vaccine, call your doctor immediately. What to do if your child has a serious reaction to a vaccine.

People with weakened immune systems may not be eligible to get the vaccine. Those with HIV, cancer, recent blood transfusions, or those on steroid medications might not be able to receive the vaccine. Also, if your child has received the first dose of the vaccine and has a severe allergic reaction, do not have your child receive the second dose. If your child is severely ill at the time he is to be vaccinated, please wait until he is better to have the vaccine administered.

There are two types of the varicella vaccine used in the US, Varivax and ProQuad. ProQuad is the MMRV vaccine and currently unavailable in the US due to low stock (as of Feb 2014).1 Varivax is the vaccine that you would receive if you are to be vaccinated in the United States. This vaccine is a live, attenuated vaccine containing a weakened version of the varicella virus. More about live, attenuated vaccines, here.

Every state in the US has laws that require children to have certain vaccinations before they enter school. During the 2011 and 2012 school year, 36 states and DC required children to receive two doses of the chickenpox vaccine or have other evidence of immunity against chickenpox before starting school.1 For more information, see State Vaccination Requirements.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that all states require children entering childcare and students starting school/college have the varicella vaccination or be able to prove that they have had the chickenpox disease and have immunity.

‘An Alien from outer space!’ Her brother laughed and scratched his face.”

The varicella vaccine is especially important in preventing outbreaks of the chickenpox in schools and daycares. Should parents stop vaccinating their children, not only are their children at risk for contracting the chickenpox, but so are those children who are unable to get the vaccine due to illnesses. Please read my post on herd immunity for more information on why vaccines protect entire communities.

After just one dose of the varicella vaccine, 97% of children 12 months to 12 years of age develop detectable memory antibodies.1 More than 90% of those children have those antibodies for at least six years.1 It is recommended that a second dose be given to children 4-6 years of age, for continued life-long protection. According to many studies, immunity after two doses of the vaccine appears to be life-long.1

The varicella vaccine became available in the US in 1995, and since then the number of hospitalizations and deaths from the chickenpox has decreased more than 90%.2 The year before the vaccine came out, there were about 4 million cases of the chickenpox in the US.2 Because it’s so contagious, almost every person in this country used to get chickenpox at some point in their lives. It’s possible that if we all keep vaccinating our kids against the chickenpox, we will have few to no cases of the chickenpox in the Unites States in the near future.

It’s easy to keep your children healthy and out of those oatmeal baths!

Resources:

- Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). www.cdc.gov

- Vaccines.gov. www.vaccines.gov

- Immunization Action Coalition. www.immunize.org

- MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. www.nlm.nih.gov

Photos taken from:

Delaney, Erin and Hanako Wakiyama. Goldie Locks has Chicken Pox. Aladdin. April 1, 2005.

2 thoughts on “Varicella (chickenpox) Vaccine”

Comments are closed.

Thanks so much!

It’s such a pain when your child has chicken pox but it’s good that there’s great info out there. Keep up the great posts.